Comissioned by Urban Wilderness as a part of The Happenings Materials: clay, dogwood, willow, bracken & others found on site

ALIGNMENT

Built from materials collected around the site, this clay stone path is the artist’s attempt to capture and temporarily shape the life cycle of Burslem Port. Made of industrial waste, clay exposed by recent fires and nearby roadworks, textured with plants and remains of human activity on the site - bricks, bottles, pieces of rope and net - they represent the quiet life of the park which Burslem Port has become since the canal branch closure in the 1960s.

Because clay, unless fired, undergoes a continuous cycle of sedimentation and erosion, the destiny of these temporary rocks is to disintegrate and for its components to return to the site they came from - a process which will begin on the day they are installed.

Referring to megalithic stone alignments or rows, a ceremonial way of route-making and one of the earliest forms of human intervention into landscapes, they naturally form a conversation with the existing concrete poles on the site, which represent a much more hostile method of defining paths - fencing. In contrast, Alignment’s purpose is to open up this wild space, to invite and guide visitors towards the natural beauty of Burslem Port.

Because clay, unless fired, undergoes a continuous cycle of sedimentation and erosion, the destiny of these temporary rocks is to disintegrate and for its components to return to the site they came from - a process which will begin on the day they are installed.

Referring to megalithic stone alignments or rows, a ceremonial way of route-making and one of the earliest forms of human intervention into landscapes, they naturally form a conversation with the existing concrete poles on the site, which represent a much more hostile method of defining paths - fencing. In contrast, Alignment’s purpose is to open up this wild space, to invite and guide visitors towards the natural beauty of Burslem Port.

THE SITE & PROJECT BACKGROUND

Burslem Port is a brownfield site in Stoke-on-Trent. Today it’s a thriving green space used by local residents. It’s currently in danger of being redeveloped.

My interest in the site begun two years before the project, in 2019, when it first became a part of my daily commute. As a pedestrian living in Stoke-on-Trent, a city with infrastructure which favours the car over any other mode of transportation, I’m continuously interested in finding alternative routes through it. There is an abundance of unofficial green spaces in the city and through walking their lazy lines for the past two years, I have been looking for ways they connect with each other. Linking with the now non-existent Etruria Valley brownfield site, Grange Park and Festival Park, Burslem Port is a part of a large central green belt, situated between Hanley and Burslem.

I recorded the life cycle of the site for two years in photographs, focusing on materials present there as well as its interesting flora. I have observed some rare species, like pinesap as well as many stunning garden escapes from nearby allotments, like Siberian Iris, China Rose, lupins and raspberries. Receiving a commission from Urban Wilderness to work on the site I already had a deep involvement with was an exciting opportunity.

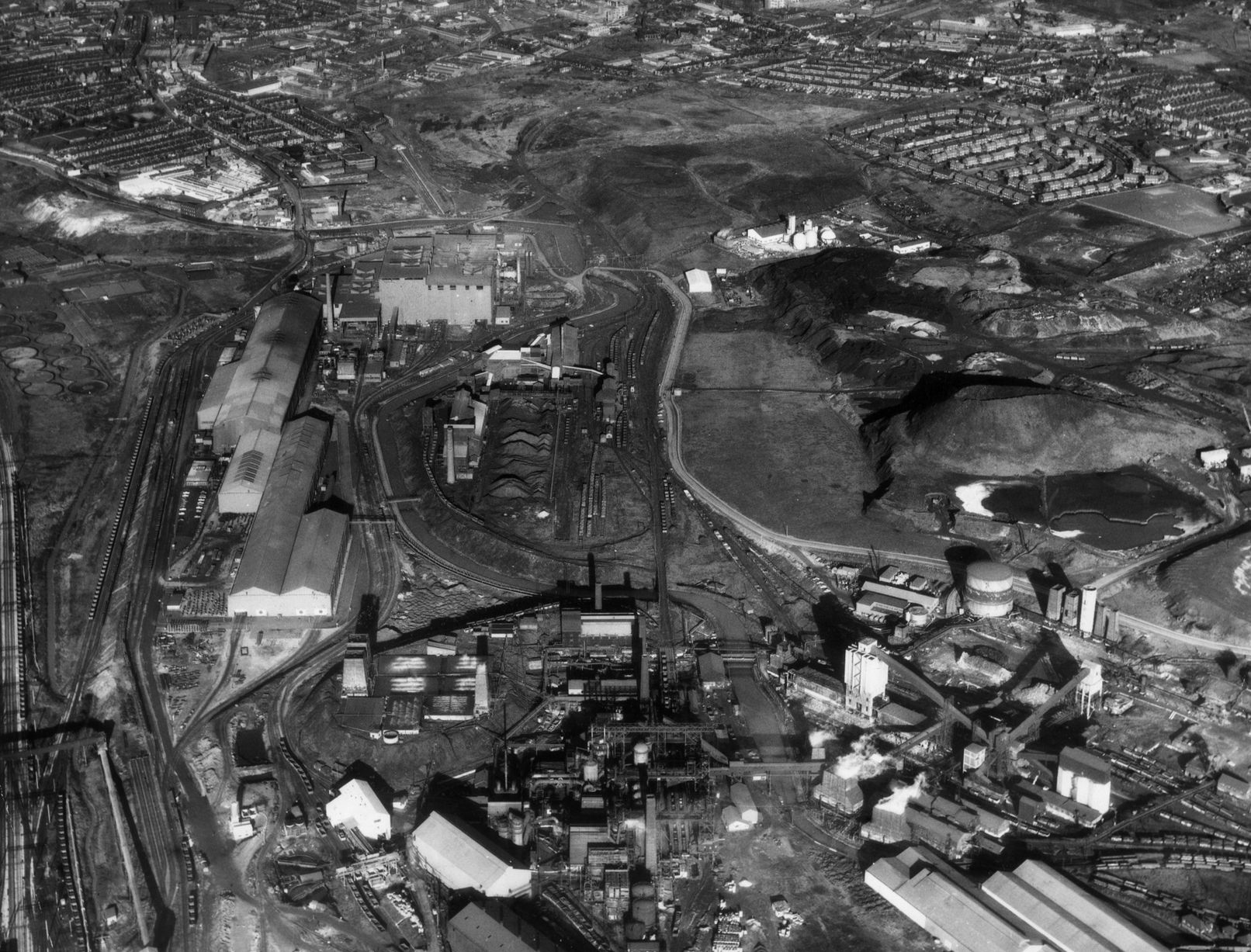

The site is composed of two distinct parts with different histories. The northernmost part used to be a canal branch, which closed in 1961 after a breach. It’s tended to by Burslem Port Trust, a group of volunteers from the area which have been working together since 1999 to reopen the canal where it once was. The remaining walls of the buildings which stood by the canal - a pottery and Co-op bakery (now torn down for a new housing development) became a place for graffiti and street artists to practice. The southern area, on the other side of Fowlea Brook which runs through it, used to be a part of a 400-acre steelworks, Shelton Bar, the slag waste from which was used to fill the canal. With the remains of an old railway and a shallow pool, filled with what’s most likely waste from the steelworks, its now predominantly used as a walkway and a spot for fishing in the canal. This area connecting with Festival Park and Etruria Valley became a site of interest for the project.

The former site of Shelton Bar has been a part of my investigations previously, most notably through glaze experiments with blast-furnace slag and use of clay exposed on the site. These were collected from Etruria Valley, which was a part of my daily commute before it started being developed into a road joining A50 with Festival Retail Park. In that process, a mound of clay was unearthed by the bulldozers, which not only provided a convenient resource for the comission but an important connection between the two sites within it - my discovery of Burslem Port happened when Etruria Valley was permanently fenced off and I had to find a new route through the area.

I was also interested by the contrasts and similarities between Burslem Port and Festival Park, another former part of Shelton Bar, which was the site of the National Garden Festival in 1986, a major effort to reclaim the contaminated land, reframe thinking around Stoke-on-Trent’s falling industry and bring investment to the city. Alongside major landscaping, it included a railway, a funicular and works from major artists like Anthony Gormley, Cornelia Parker and Maggie Howarth. A large area of where the Garden Festival took place is now a retail park but a small part still remains green, with original landscaping and exotic plants peeking through. In recent years it’s undergone many reclamation projects by artists, including the 2016 Lost Gardens of Stoke-on-Trent project, which aimed to consider Stoke-on-Trent for City of Culture in 2021. Meanwhile, Bruslem Port has largely been left to its own devices.

The differences and similarities between the three sites today - the shared and separate elements of their history, common geology, exotic plants among the wilderness, the attention they receive and have received in the past - all of that strongly informed the shape of Alignment.

![]()

The former site of Shelton Bar has been a part of my investigations previously, most notably through glaze experiments with blast-furnace slag and use of clay exposed on the site. These were collected from Etruria Valley, which was a part of my daily commute before it started being developed into a road joining A50 with Festival Retail Park. In that process, a mound of clay was unearthed by the bulldozers, which not only provided a convenient resource for the comission but an important connection between the two sites within it - my discovery of Burslem Port happened when Etruria Valley was permanently fenced off and I had to find a new route through the area.

I was also interested by the contrasts and similarities between Burslem Port and Festival Park, another former part of Shelton Bar, which was the site of the National Garden Festival in 1986, a major effort to reclaim the contaminated land, reframe thinking around Stoke-on-Trent’s falling industry and bring investment to the city. Alongside major landscaping, it included a railway, a funicular and works from major artists like Anthony Gormley, Cornelia Parker and Maggie Howarth. A large area of where the Garden Festival took place is now a retail park but a small part still remains green, with original landscaping and exotic plants peeking through. In recent years it’s undergone many reclamation projects by artists, including the 2016 Lost Gardens of Stoke-on-Trent project, which aimed to consider Stoke-on-Trent for City of Culture in 2021. Meanwhile, Bruslem Port has largely been left to its own devices.

The differences and similarities between the three sites today - the shared and separate elements of their history, common geology, exotic plants among the wilderness, the attention they receive and have received in the past - all of that strongly informed the shape of Alignment.

MATERIALS AND TOOLS

The installation was built exclusively from materials found on and around the site. Following a period of study and observation, materials which could be used for tools and making were identified.

The primary material used in Alignment is local clay of basaltic origins, Etruria Marl, which seam runs through most of the Midlands region of England. Associated with coal, this clay is fundamental to the industrial history of the site. Three tons of the clay were shifted in a wheelbarrow from nearby roadworks, where the bulldozers cleared a large deposit of the material.

Because the work wasn’t fired, this was an opportunity to celebrate the nature of the material in its raw state. Different levels of oxidation in the clay produce varying colours in the seam - red, yellow and grey. Some of the clay was dried and carefully divided into chunks of corresponding colours. They were subsequently mixed with water to produce slips which were used on the surface of the megaliths and placed in pools around the central stone.

Dogwood and willow growing on the site in abundance were used to build internal structures of the megaliths. As common and fast-growing shrubs / trees, they were an ideal resource. Popular in basket-making, their flexible branches were suitable to weave around frames made from diseased trees which were cut down on the site.

The installation was built exclusively from materials found on and around the site. Following a period of study and observation, materials which could be used for tools and making were identified.

The primary material used in Alignment is local clay of basaltic origins, Etruria Marl, which seam runs through most of the Midlands region of England. Associated with coal, this clay is fundamental to the industrial history of the site. Three tons of the clay were shifted in a wheelbarrow from nearby roadworks, where the bulldozers cleared a large deposit of the material.

Because the work wasn’t fired, this was an opportunity to celebrate the nature of the material in its raw state. Different levels of oxidation in the clay produce varying colours in the seam - red, yellow and grey. Some of the clay was dried and carefully divided into chunks of corresponding colours. They were subsequently mixed with water to produce slips which were used on the surface of the megaliths and placed in pools around the central stone.

Dogwood and willow growing on the site in abundance were used to build internal structures of the megaliths. As common and fast-growing shrubs / trees, they were an ideal resource. Popular in basket-making, their flexible branches were suitable to weave around frames made from diseased trees which were cut down on the site.

Tools for surface treatment were also made from objects found on walks in Burslem Port. Some were natural materials, rocks and plants, like the invasive Japanese Knotweed which is currently colonising the site. Others were remnants of human activity on the site - bottle caps, pieces of spray cans and burned tyres.

Timeline

July 2021 | Three tons of clay wheelbarrowed out of nearby roadworks and placed in rubble bags on site

August 2021 | Objects and plants collected in Burslem Port are made into tools

September 2021 | Local clay is processed to produce coloured slips

October 2021 | Willow and dogwood supports are built on site in Burslem Port

October 2021 | The structures are clad in unprocessed clay and painted with slips

Photography by Glen Stoker, Jenny Harper & artist

Many thanks to Glen Stoker, Sandra Aydin, Brian Dickenson, Joanne Ayre, Steve Wood & Urban Wilderness